My Journey in Finance: How to Build a Momentum Fund

Disclaimer: Your capital is at risk. This is not investment advice.

Last week, I kicked off this new series by introducing why momentum works. Please have a look at Why Momentum Works before you carry on.

To build a global momentum fund, you can’t look at every stock in the world; you have to cut that down to size. Too many stocks in your universe will lead to too many stocks in your portfolio, and “diworsified” portfolios don’t perform.

Bearing in mind that you want the stocks to be liquid and easy to trade, a good starting point is to cut down the universe to a workable number of companies, such as the 1,416 constituents of the world index. Using an index is helpful because the index company brings in new companies and ejects old ones, keeping the investment universe up to date. Having a universe like this is one less thing to think about.

Alternatively, you could choose a single country or region, such as the S&P 500 or the EuroStoxx600. That’s fine, but in the 1980s, the market leadership was dominated by Japanese companies, and in the noughties, it was in the emerging markets. Narrowing the geographic reach too much can mean the strategy misses the greatest of trends. I would try to keep it global.

You then find a data source for historical share prices, adjust them where necessary (share splits, corporate actions, dividends etc.), convert them into the same currency and measure them against an index, such as the world index. Keep the price data and the index in the same currency, and the US dollar becomes the obvious choice. But it wouldn’t matter if you chose the Turkish Lira or anything else, provided both the companies and the index were measured in the same way.

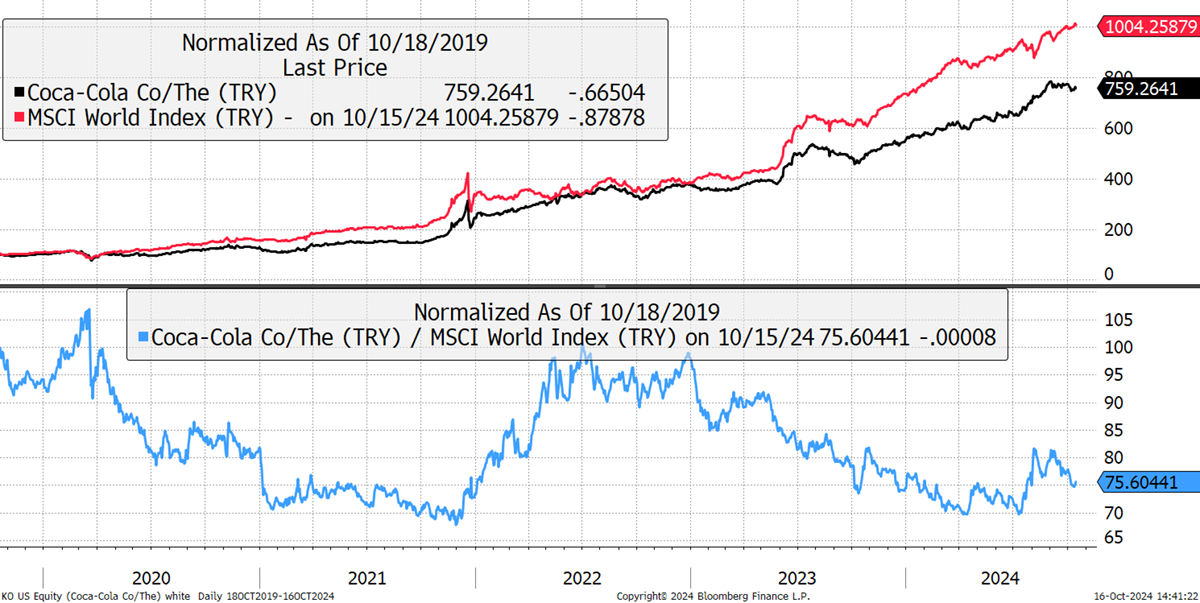

For example, Coca-Cola (black) and the world index (red) in Lira show both up 10x and 7x due to the weak Lira, but Coca-Cola has lagged the world, being 75 (blue) after five years.

Coca-Cola, World Index in Turkish Lira

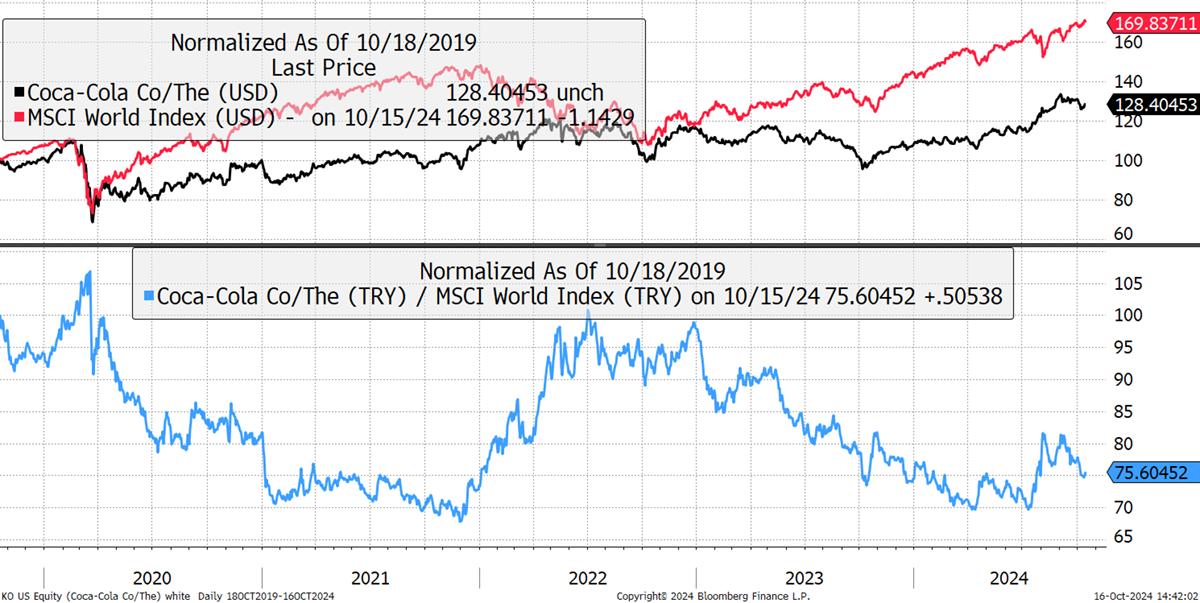

Repeating the same exercise in US dollars, Coca-Cola (KO black) and the world index (red) in USD show both up 70% and 28%, which is up by much less due to a stronger US dollar. Yet, the blue line, the price relative, is identical in both cases, at 75. This is an important point because “price relative” is a ratio and is the same in every currency. What is crucial is that the stocks and the index must all be measured in the same currency, but it doesn’t matter which one.

Coca-Cola, World Index in Turkish USD

Given that trends can change so much by currency, the focus is on the blue line, the price relative. Our global trend fund is searching for the strongest trends wherever they can be found. The example of KO shows a stock that has lagged the market over five years. Since the blue line reads 75, KO has underperformed the market by 25%.

Being a defensive company selling soft drinks, it outperformed the stockmarket in 2022 (blue line rising) when the market was falling. That is another way of identifying defensive stocks, as they have a habit of doing well, when things are going badly, and many fund managers have made a living out of embracing defensive stocks. A discussion for another day. The point is that KO does not currently have relative strength, so it will not be a candidate for this exercise. Perhaps we can find something that is.

NVIDIA

Here’s a well-known market leader, the AI chip maker NVIDIA (NVDA). It floated in 1999, and $100 invested back then would today be worth $343,000. The price relative is currently strong, but over three decades, it has come about in three stages.